AP

AP

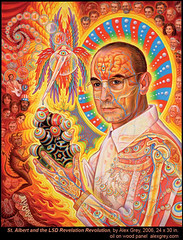

Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann discovered LSD in 1938

(FILES) This undated handout file picture released by Novartis laboratories shows scientist Dr Albert Hofmann showing a model of the LSD molecule. Swiss authorities said on April 30, 2008 that Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who discovered the now-banned hallucinogenic drug LSD that was an icon of the Hippy movement, has died at the age of 102.

NEW YORK - Albert Hofmann, the father of the mind-altering drug LSD whose medical discovery grew into a notorious "problem child," died Tuesday. He was 102.

Hofmann died of a heart attack at his home in Basel, Switzerland, according to Rick Doblin, president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, in a statement posted on the association's Web site.

Hofmann's hallucinogen inspired — and arguably corrupted — millions in the 1960's hippy generation. For decades after LSD was banned in the late 1960s, Hofmann defended his invention.

"I produced the substance as a medicine ... It's not my fault if people abused it," he once said.

The Swiss chemist discovered lysergic acid diethylamide-25 in 1938 while studying the medicinal uses of a fungus found on wheat and other grains at the Sandoz pharmaceuticals firm in Basel.

He became the first human guinea pig of the drug when a tiny amount of the substance seeped on to his finger during a repeat of the laboratory experiment on April 16, 1943.

"I had to leave work for home because I was suddenly hit by a sudden feeling of unease and mild dizziness," he subsequently wrote in a memo to company bosses.

"Everything I saw was distorted as in a warped mirror," he said, describing his bicycle ride home. "I had the impression I was rooted to the spot. But my assistant told me we were actually going very fast."

Image by ddaa via FlickrOne trip leads to another

Image by ddaa via FlickrOne trip leads to another

Three days later, Hofmann experimented with a larger dose. The result was a horror trip.

"The substance which I wanted to experiment with took over me. I was filled with an overwhelming fear that I would go crazy. I was transported to a different world, a different time," Hofmann wrote.

There was no answer at Hofmann's home on Tuesday and a person who answered the phone at Novartis, a former employer, said the company had no knowledge of his death.

Hofmann and his scientific colleagues hoped that LSD would make an important contribution to psychiatric research. The drug exaggerated inner problems and conflicts and thus it was hoped that it might be used to recognize and treat mental illness like schizophrenia.For a time, Sandoz sold LSD 25 under the name Delysid, encouraging doctors to try it themselves. It was one of the strongest drugs in medicine — with just one gram enough to drug an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people for 12 hours.

Hofmann discovered the drug had a similar chemical structure to psychedelic mushrooms and herbs used in religious ceremonies by Mexican Indians.

Symbol of the '60s

LSD was elevated to international fame in the late 1950s and 1960s thanks to Harvard professor Timothy Leary who embraced the drug under the slogan "turn on, tune in, drop out." The film star Cary Grant and numerous rock musicians extolled its virtues in achieving true self discovery and enlightenment.

But away from the psychedelic trips and flower children, horror stories emerged about people going on murder sprees or jumping out of windows while hallucinating. Heavy users suffered permanent psychological damage.

The U.S. government banned LSD in 1966 and other countries followed suit.Hofmann maintained this was unfair, arguing that the drug was not addictive. He repeatedly maintained the ban should be lifted to allow LSD to be used in medical research.

‘My problem child’

He himself took the drug — purportedly on an occasional basis and out of scientific interest — for several decades.

"LSD can help open your eyes," he once said. "But there are other ways — meditation, dance, music, fasting."

Even so, the self described "father" of LSD readily agreed that the drug was dangerous if in the wrong hands. This was reflected by the title of his 1979 book: "LSD - my problem child."